The original 7 deadly sins emerged from the Desert fathers, ascetic monks and hermits, who sought to live virtuous lives, often removed from society and living in the deserts of Egypt. Many of them went to extreme lengths to achieve their goal, like Simeon Stylites who spent 37 years living on top of a pillar 50 feet high in what is now Syria.

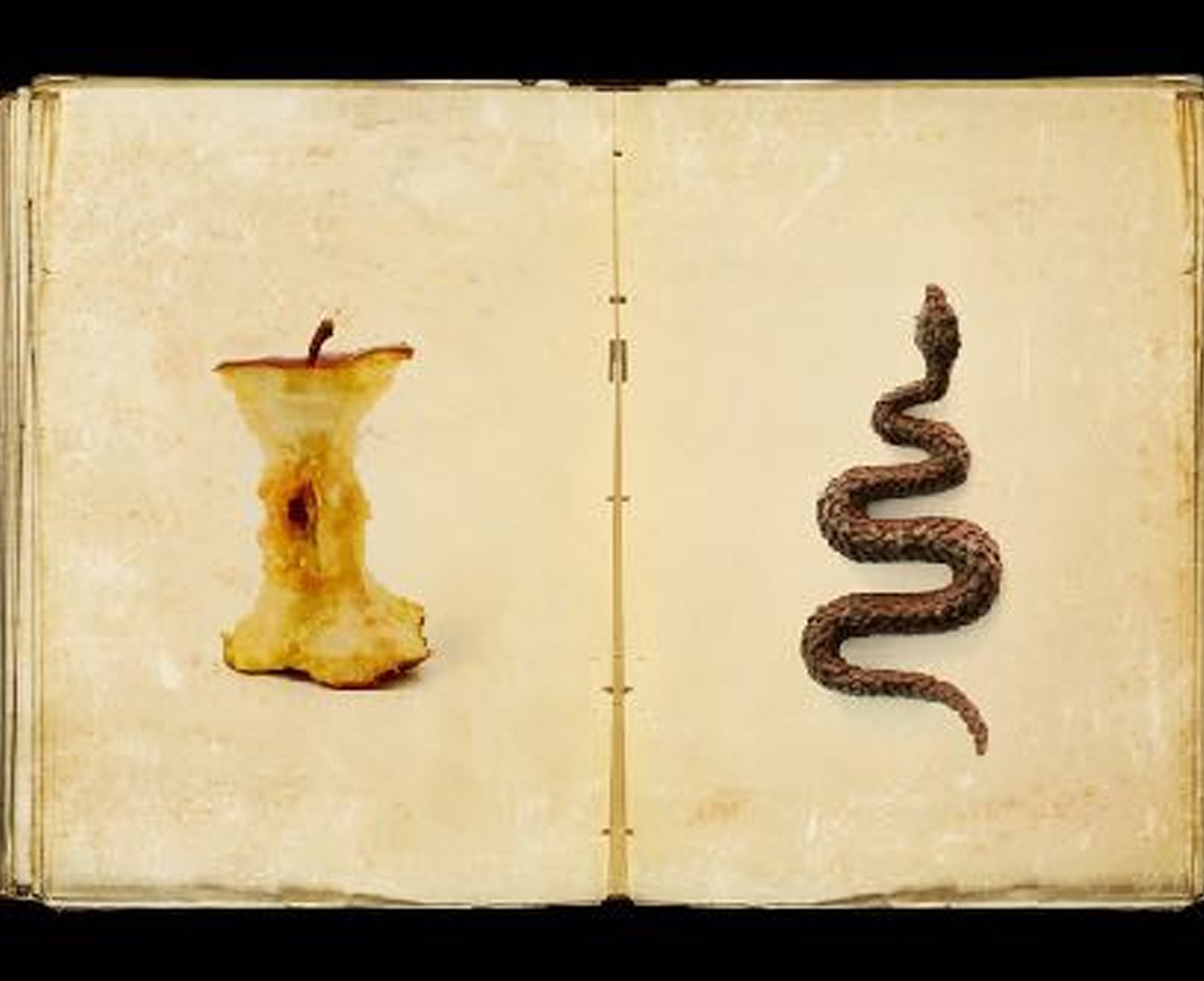

They later became a key part of Catholic Christianity, being used in confession, devotional aids, sermons, literature and the arts. The original 7 deadly sins in English are; pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath and sloth. They were seen as the chief sins that people struggle with and if left unchecked give birth to other weakness. I could have just used the original list as they to can screw up leaders and the organisations they lead but instead, I wanted to list things, I think leaders are subtly susceptible to from my 20 plus years of being a leadership practitioner.

Hubris

Hubris means excessive pride or arrogance. It originally comes from Ancient Greece and

conveyed the idea of a person overstepping the mark, of acting godlike and thus breaking divine order. In other words, thinking of themselves more highly than they ought. These hubris thoughts, would lead to foolish action and result in shame. The idea of pride coming before a fall was a theme throughout Greek Tragedy.

These thoughts of hubris emerge in us often because of a successful track record of winning and achievement. Leaders are particularly susceptible to them because they are

achievers and have built track records of success. It is fuelled by good press, perks of the job, privilege, sycophants and favourable conditions. These can all lead to a puffed-up view of ourselves, our abilities and lead us to overstep the mark.

The former executives of Enron, Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay who were convicted on various charges of fraud, conspiracy and insider trading were part of one of the largest bankruptcies of all time, estimated at 23 billion dollars in liabilities.

“Our performance has never been stronger; our business model has never been more robust; our growth has never been more certain; and most importantly, we have never had a better nor deeper pool of talent throughout the company,” Lay said in an email to a colleague weeks prior to the collapse.`

Jeff Skilling had once boasted that all he had known was success, hence in part revealing the genesis of his hubris.

Enron failed for a number of well-documented reasons but one was the culture of hubris that had been created at the executive table where questions regarding unusual accounting methodologies were ignored, a belief of invincibility, extravagance, and that they were building a ‘new economy’, one that defied the rules of the old. Unfortunately cash flow and operating ethically still matter as they found out.

In history we see examples of Hubris with Napoleon in 1812 invading Russia to get Emperor Alexander 1 to bow the knee, he went in with 600,000 men and came back with around 100,000, losing his army and empire. Hitler’s hubris also included a failed Russian campaign that involved him not listening to his generals and taking over military planning even though he had little experience. We see Hubris in sports with the Lance Armstrong doping scandal, unfortunately, one among many flawed athletes.

What are some of the signs of hubris?

Playing loose with rules/policies/ ethics as if they don’t apply to them or this situation. Attacking perceived threats aggressively.

Recruiting and building a team of insiders who all think the same and reinforce the hubristic view. Refusing to listen to contrary opinion or outside advice.

The need to display symbols of success. A win at any costs mentality.

Language is of superiority.

In Ancient Rome if a general had a particularly successful military campaign, the Senate might grant a “Triumph”, a march through the centre of Rome. A “Triumph” was a glorious occasion often followed by a circus with the battles being reenacted.The march would have been a sight to behold with musicians, colourful banners, the general would ride a

high sided chariot pulled by four horses, dressed in royal colours and covered with red paint depicting the gods of Jupiter and Mars. He would be followed by soldiers in their regalia, animals captured in the lands conquered, conquered generals and other slaves, as well as the plunder of war. The crowds would line the streets and cheer. In the midst of all of this, a slave would be behind the general holding a golden crown over his head whispering in his ear “Respice post te, hominem memento te.” “Look behind you, and remember that you are but human.” And who were behind him? The soldiers who fought hard to win the battles and the conquered generals. Here was a visual reminder to keep his pride in check. His success firstly has not been due to him alone but to his army, perhaps his superior technology of warfare, and to other factors. Likewise, by looking behind he sees the conquered generals and is struck with the sobering thought, if things had not been favourable it could have been he in chains.

The antidote for Hubris is humility, having a right view of ourselves and our current reality.

Perfectionism

Excellence is doing the best you can, with the resources you have available, in a suitable time frame, to get the job done. Perfectionism is abusing the same resources, in an attempt to quiet the voice of insecurity.

They can both look the same but they come from very different heart motives. One is stewardship while the other is squandering.

Version 1.0 is often good enough and fixes, updates and patches can be made along the way if needs are.

The antidote to perfectionism is stewardship.

Impatience

“A moment of patience can prevent a great disaster and a moment of impatience can ruin a whole life.” Chinese Proverb

We live in a fast-paced world, where leaders are prized who can make decisions quickly and under pressure Agility, responsiveness to market and the ability to turn on a dime are all desirable in our time and age but need to be married to wisdom and long-term strategic thinking.

A Pew Research poll exploring the internet and American linked peoples hyper-connectivity to technology to an ‘increase in self -gratification and a loss of patience’.

The impatience I touch on here is not the mild annoyance or peevishness with delays or being inconvenienced. We all suffer these. It’s more a ‘chronic impatience’,

Impatience in leadership can cause leaders to focus on projects that will have an immediate payoff, quick turn around and not invest themselves into those activities that will outlast them and ultimately leave the organisation in better shape years down the track.

I liken leadership to renovating a house, an impatient leader will focus on those tasks that are easiest and have the quickest payoff. Perhaps decorate the living areas, create a beautiful space, a new lick of paint, some new drapes. There will be deep satisfaction in getting this done, others will notice, it will look good and is easy to point to. The wise leader, however, thinks long term and focuses on the longevity and sustainability of the building. It’s often those parts of the building that are hidden from view, and far from sexy.

The wiring, the foundations, the roof. They are tasks that might not be glamorous, nor easy to point to but ultimately they mean the building will keep standing.

A large national organisation constantly needed middle managers, so they spent large amounts of money hiring a recruitment company to attract talent both in the domestic market and the overseas market. This at times had varying degrees of success however the real human resource issue needs in the organisation were ignored because it required a long-term strategic approach willing to explore without blame the culture of the organisation, explore the root causes of poor middle management retention and develop pathways of recognising leadership talent in the organisation and creating a clear pathway to recruit from within the ranks.

The antidote to impatience in leadership is to discipline one’s thinking to think through the lens of medium-term and long term strategic thinking.

Entitlement

Entitlement can kick in because we feel owed. We have ‘earned this’, ‘deserve this’. It can occur when we act like owners rather than stewards. Perhaps we have been there for a long time, perhaps we feel slighted, or perhaps we think we have finally arrived.

One of my favourite books on leadership was written by Robert Townsend, former Avis

CEO, ‘Up the Organisation.” In the book, he challenges the culture of entitlement.

“True leadership must be for the benefit of the followers not the enrichment of the leaders.” Robert Townsend.

Several years ago, I had the unfortunate incident of finding myself seated next to a politician on a plane flight. The way he treated the flight attendant was embarrassing, He was rude, with no “please” or “thank you”, he did not respond to me when I greeted him but merely grunted. He oozed arrogance and an air of superiority. It was ugly to observe and I suspect he was oblivious to his behaviour. I thought, “I bet if your mother was here she would give you a clip around the ears and remind you of who you really are.”

Leaders are all susceptible to a sense of entitlement, most have worked hard to get where they are, it doesn’t take long to get used to the perks that come with the job, sitting at the pointy end of the plane, nice hotels, an expense account, a share option, company car, the lifestyle. Leaders can focus on these benefits rather than stewarding the work they have been entrusted with.

Leadership by its very nature is the complete opposite of entitlement, its entrustment, which requires times of self-sacrifice for the sake of the wider mission.

Signs of entitlement may include some of the following; A focus on rights over responsibilities.

Think what is in their personal best interests rather than the best interests of the organisation. Think rules, policies and procedures no longer apply to them, although they see them still applying to their teams.

Expects the benefits of an owner without the costs of an owner

A sense of anger if treated slightly less than one is accustomed to. insistence on titles.

Insistence on perks. Hypersensitivity.

Hostility to newcomers and anyone seen as a threat to their privilege.

Accepting pay raises and bonuses even when the organisation is underperforming, and/or staff are not being compensated adequately or fairly.

The antidote of entitlement is service. Servant leaders are interested in what is best for the organisation, their staff and their clients as opposed to self-interest.

Cowardice

Leadership by its nature requires courage. It takes courage to steer the ship through storms, to steer it towards its desired future. It takes courage to look at the issues no matter how bad, to face reality, to change, to confront and to make decisions.

Good leaders learn to live with the uncomfortable pit of fear in their stomach, they have learnt to accept it as a normal part of leadership and by choosing to recognise it as normal, disempower the feeling.

It reminds of the story about Martin the Luther the Monk who it was said, was awoken one night in his sleep to see the devil at the end of his bed. Luther took one look at the devil and said, “Oh it is only you.” Then went back to sleep.

The antidote to cowardice is making friends with fear.

Over-Optimism

Psychologists will tell you there is a lot of benefits to being a “cup half full” type of person. The person who is optimistic and positive has a better chance of overcoming obstacles, greater resilience and a greater chance of achieving the outcomes in life they want. Good leaders are full of optimism about the organisation and the people they have the honour of leading.

However good leaders also have to put on their glasses that are able to critically think through a situation, to ask hard and at times uncomfortable questions, to hope for the best but plan for the worse.

I have been guilty of over-optimism in a role, I was asked to oversee a subsidiary that had 13 years of history and had been running at a loss for all of those years, running a significant budget deficit. In examining the work, I fell in love with it as I witnessed first hand the power of good it could do in making people’s lives better. I was tasked with setting up its own governance and to make it financially sustainable, changing the funding model from a patronage model to one reliant on individual donors. To cut a long story short, we failed. I had thought the changes we made to make the model more cost-effective would also make it an attractive proposition to funders, but we had underestimated the time needed to bed in the change, lacked skill sets in certain key areas, and failed to understand the changing market within the funding space. In the end, we ran out of runway and ended up closing the organisation down. We had been over-optimistic that we could succeed with less resource, where an organisation that had run it for 13 years with a budget deficit had also tried and failed. I had been blinded by my over-optimism.

The owners and captain of the Titanic were over-optimistic, resulting in having on board only enough lifeboats for half of their passengers.

The antidote to over-optimism is to develop critical thinking.

Acquiescing

To ‘acquiesce’, has some of the following words and phrases associated with it; ‘to submit or comply silently’, to ‘cave in’, ‘yield’, ‘bend’, ‘capitulate’, ‘accede’.

I could go on but you get the idea. The qualities denote something of passivity. As a leader, you are appointed and paid to lead.

You do no one any good by being passive. Over many years I have sat in governance meetings in a wide variety of setting, at times I have been amazed by people who are on boards who occupy a seat but are passive in their roles, they say little or nothing at all, they always agree with the majority. I have pulled several aside at times and told them,

“You are not doing the organisation a favour by being silent, you have been invited to sit at this table because of your experience, skills and much-needed viewpoint.”

Still, other times I have seen leaders allow others to run roughshod over their sphere of leadership, trampling over their role and responsibilities and creating carnage along the ways.

If you don’t want to lead, stand down, step aside and do something you want to do. If you do want to lead but find yourself acting passively and notice signs of acquiescing in you then I would suggest the following.

Find your voice. I don’t’ care how, but leadership requires a voice.

Understand your role, responsibilities and sphere of governance and the decisions that are yours to make. You might find the following metaphor helpful. If you liken your sphere/role to that of a property. Ask yourself the following. Where are the boundaries of the property? Who do I share a fence line with? What are decisions solely mine to make? What

decisions are not mine to make? What decisions are to be made jointly? What decisions are not made by me but influence my property, what can I do about that to ensure good decisions are made? What property rights do I have? What are my responsibilities? How do I leave the property in a better state than how I found it? You get the idea.

Back yourself, your knowledge, ideas, skill set and ideas. Believe in your position and idea until someone offers a genuinely better alternative.

So there you go, my 7 deadly sins of leadership; Hubris, perfectionism, impatience, entitlement, cowardice, over-optimism and acquiescing. They are not as dramatic as the original 7 deadly sins nor lead inspire art or fuel the imagination like Dante’s “Inferno” but hopefully it might help you to do a quick self-audit and cause you to keep leading out of excellence and wisdom.

© 2019 G M Brock